Research overview

“Whoever owns land has thus assumed, whether he knows it or not, the divine functions of creating and destroying. . .” - Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

I am fascinated by all the ways in which humans manage the land, from protection to extraction, particularly for agriculture and food security. These land management decisions impact who eats what, while also modifying the land and water that flows on and through it. Land management has even resulted in wholly novel ecosystems with distinct Earth system interactions. As an Earth system scientist and modeler, I take a particular interest in how decisions of land management, in all the ways they are influenced and manifest, can modify regional climates and environments. Understanding how management decisions impact land-climate-water interactions is critical to creating more climate-resilient land management systems in an era of increasing anthropogenic climate change and extremes. Furthermore, decisions of land management are shaped by myriad factors that, in our current global society, extend beyond individual ownership to the whims of global markets and remote demands. Therefore, approaches to develop more climate-resilient modes of land management must deeply engage with human dimensions to evaluate both socioeconomic and biophysical co-benefits trade-offs – a key goal of my research.

My research is broadly separated by the following questions:

1) How does land management, particularly agriculture, impact regional climates and drive environmental change?

Soil Carbon Losses Reduce Soil Moisture in Global Climate Model Simulations

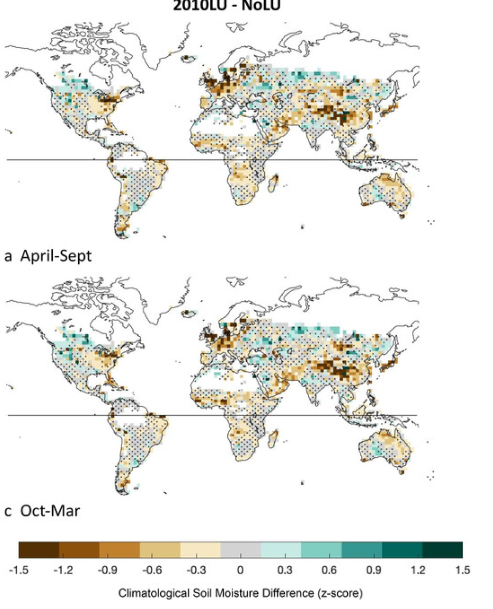

Soil moisture (130-yr) climatological anomalies (z score) relative to the NoLU experiment for the (a) 2010LU experiment, April–September; (b) 30ST experiment, April–September; Stippled areas are not statistically significant.

Most agricultural soils have experienced substantial soil organic carbon losses in time. These losses motivate recent calls to restore organic carbon in agricultural lands to improve biogeochemical cycling and for climate change mitigation. Declines in organic carbon also reduce soil infiltration and water holding capacity, which may have important effects on regional hydrology and climate. To explore the regional hydroclimate impacts of soil organic carbon changes, we conduct new global climate model experiments with NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE that include spatially explicit soil organic carbon concentrations associated with different human land management scenarios. Compared to a “no land use” case, a year 2010 soil degradation scenario, in which organic carbon content (OCC; weight %) is reduced by a factor of ∼0.12 on average across agricultural soils, resulted in soil moisture losses between 0.5 and 1 temporal standard deviations over eastern Asia, northern Europe, and the eastern United States. In a more extreme idealized scenario where OCC is reduced uniformly by 0.66 across agricultural soils, soil moisture losses exceed one standard deviation in both hemispheres. Within the model, these soil moisture declines occur primarily due to reductions in porosity (and to a lesser extent infiltration) that overall soil water holding capacity. These results demonstrate that changes in soil organic carbon can have meaningful, large-scale effects on regional hydroclimate and should be considered in climate model evaluations and developments. Further, this also suggests that soil restoration efforts targeting the carbon cycle are likely to have additional benefits for improving drought resilience.

Learn more here: McDermid et al 2022

Distinct influences of land-cover and land-management on seasonal climate

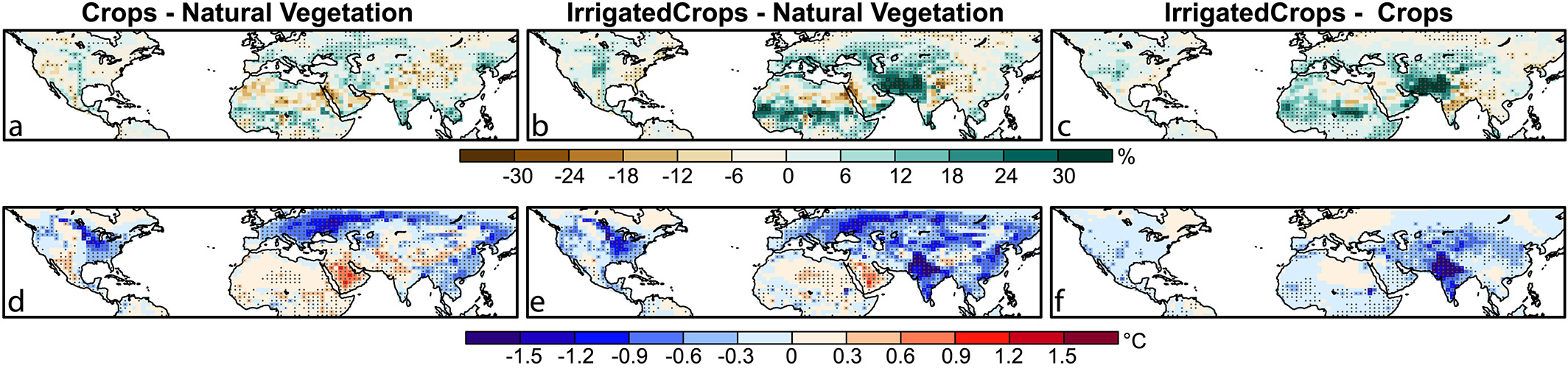

Anthropogenic land-use and land-cover change is primarily represented in climate model simulations through prescribed transitions from natural-vegetation to cropland or pasture. However, recent studies have demonstrated that land-management practices, especially irrigation, have distinct climate impacts. Here, we disentangle the seasonal climate impacts of land-cover change and irrigation across areas of high agricultural intensity using climate simulations with three different land-surface scenarios: 1) natural-vegetation cover/no irrigation, 2) Year 2000 crop-cover/no irrigation, and 3) Year 2000 crop-cover and irrigation rates. We find that irrigation substantially amplifies land-cover induced climate impacts but has opposing effects across certain regions. Irrigation mostly causes surface cooling, which substantially amplifies land-cover change-induced cooling in most regions except over Central, West and South Asia, where it reverses land-cover change induced warming. Despite increases in net surface radiation in some regions, this cooling is associated with enhancement of latent relative to sensible heat fluxes by irrigation. Similarly, irrigation substantially enhances the wetting influence of land-cover change over most regions including West Asia and the Mediterranean. The most notable contrasting impacts of these forcings on precipitation occur over South Asia, where irrigation offsets the wetting influence of land-cover during the monsoon season. Changes in regional circulations and moist static energy induced by these forcings contribute to their precipitation impacts and are associated with differential changes in surface and tropospheric temperature gradients and moisture availability. These results emphasize the importance of including irrigation forcing to evaluate the combined climate effects of land-surface changes for attributing historical changes and managing future impacts.

Learn more here: Singh, McDermid 2018

2) How do climate and environmental change impact terrestrial ecosystems, particularly agroecosystem production and resulting food security, particularly in monsoonal climates, drylands, and the most vulnerable regions?

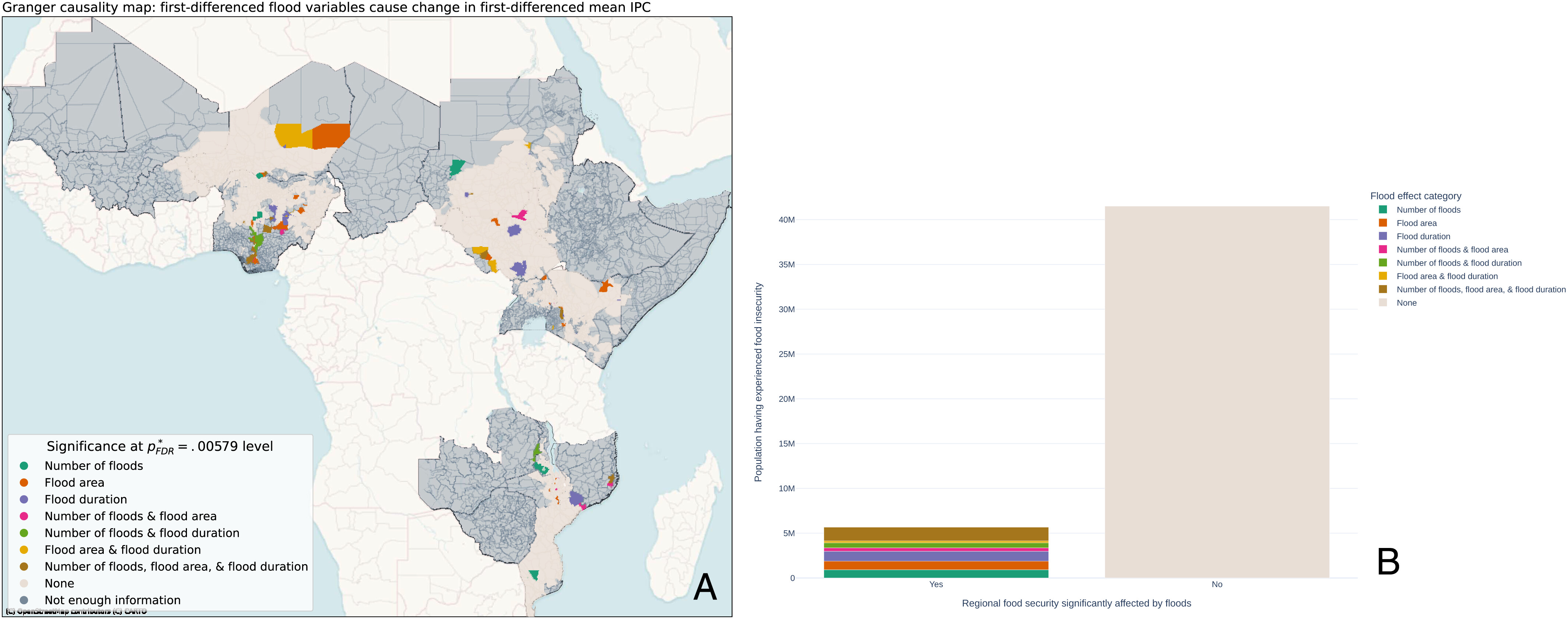

The impact of flooding on food security across Africa

Recent record rainfall and flood events have prompted increased attention to flood impacts on human systems. Information regarding flood effects on food security is of particular importance for humanitarian organizations and is especially valuable across Africa's rural areas that contribute to regional food supplies. We quantitatively evaluate where and to what extent flooding impacts food security across Africa, using a Granger causality analysis and panel modeling approaches. Within our modeled areas, we find that ∼12% of the people that experienced food insecurity from 2009 to 2020 had their food security status affected by flooding. Furthermore, flooding and its associated meteorological conditions can simultaneously degrade food security locally while enhancing it at regional spatial scales, leading to large variations in overall food security outcomes. Dedicated data collection at the intersection of flood events and associated food security measures across different spatial and temporal scales are required to better characterize the extent of flood impact and inform preparedness, response, and recovery needs

Learn more here: Reed et al 2022

Moisture and temperature influences on nonlinear vegetation trends in Serengeti National Park

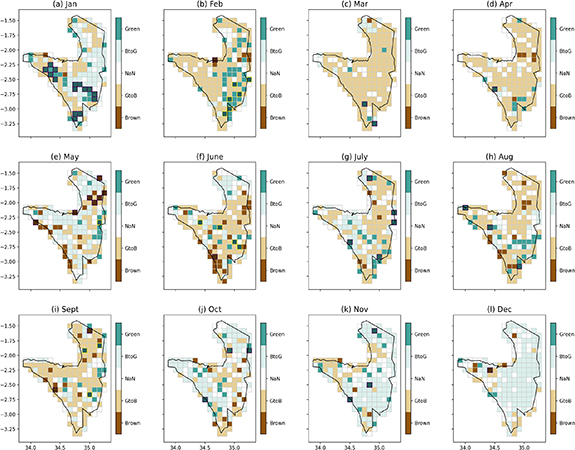

Monthly plots of LAI3g Trend categorization: Brown = monotonic browning; GtoB = reversal from greening to browning; BtoG = reversal from browning to greening; Green = monotonic greening; NaN denotes the remaining Trend has more than one extrema and cannot be classified in any of these categories; overplotted on some grid cells is black hatch lines, denoting that our surrogate test indicates the monotonic greening or browning Trend is significant at 0.05 level.

While long-term vegetation greening trends have appeared across large land areas over the late 20th century, uncertainty remains in identifying and attributing finer-scale vegetation changes and trends, particularly across protected areas. Serengeti National Park (SNP) is a critical East African protected area, where seasonal vegetation cycles support vast populations of grazing herbivores and a host of ecosystem dynamics. Previous work has shown how non-climate drivers (e.g. land use) shape the SNP ecosystem, but it is still unclear to what extent changing climate conditions influence SNP vegetation, particularly at finer spatial and temporal scales. We fill this research gap by evaluating long-term (1982–2016) changes in SNP leaf area index (LAI) in relation to both temperature and moisture availability using Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition and Principal Component Analysis with regression techniques. We find that SNP LAI trends are nonlinear, display high sub-seasonal variation, and are influenced by lagged changes in both moisture and temperature variables and their interactions. LAI during the long rains (e.g. March) exhibits a greening-to-browning trend reversal starting in the early 2000s, partly due to antecedent precipitation declines. In contrast, LAI during the short rains (e.g. November, December) displays browning-to-greening alongside increasing moisture availability. Rising temperature trends also have important, secondary interactions with moisture variables to shape these SNP vegetation trends. Our findings show complex vegetation-climate interactions occurring at important temporal and spatial scales of the SNP, and our rigorous statistical approaches detect these complex climate-vegetation trends and interactions, while guarding against spurious vegetation signals.

Learn more here: Huang, McDermid et al. 2021

3) What is the meaningful solution space for meeting land management goals, particularly inclusive of food security, climate adaptation and climate mitigation?

The Impact of Drought on Terrestrial Carbon in the West African Sahel: Implications for Natural Climate Solutions

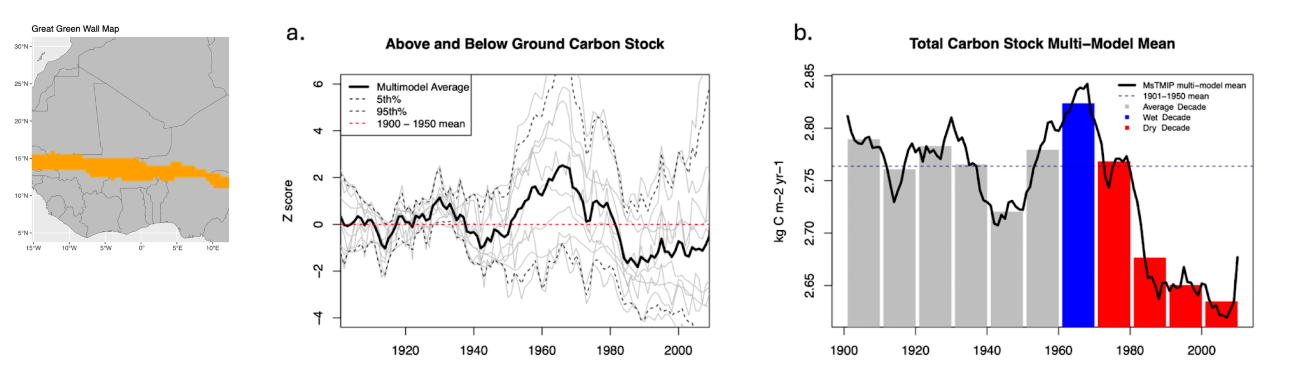

Above and below ground modeled carbon stock model response from 1901 - 2010. Panels depict (a) z-scores (after taking difference in row 5 Table 2 to identify impact of all forcings) of relative to the 1901-1950 standard deviation and mean of combined live biomass and soil carbon stocks. Individual models are shown in light gray lines, 5th and 95th percentiles are shown in dashed black lines, the multi-model mean is shown in the bold black line, and the 1901-1950 mean value is shown in the red dashed line on each plot; (b) bars show multi-model average of decadal means in combined biotic and soil carbon stock across models in native units, bold black line shows the interannual values of multi-model average in combined biotic and soil carbon stock (native units), and dashed line shows the multi-model 1900-1950 average;

Terrestrial ecosystems store more than twice the carbon of the atmosphere, and play a critical role in climate change mitigation. This has led to a proliferation of land-based carbon sequestration efforts, such as reforestation and afforestation, including semi-arid regions like the West African Sahel (WAS). However, we are currently lacking comprehensive assessment of the long-term viability of these ecosystems’ carbon storage in the context of increasingly severe climate extremes. The WAS is particularly prone to recurrent and disruptive extremes, such as the persistent and severe late-20th century drought. We assessed the response and recovery of WAS carbon stocks and fluxes to the late-20th century drought and the subsequent rainfall recovery by leveraging a suite of terrestrial ecosystem models. While multi-model mean carbon fluxes (e.g., gross primary production, respiration) recovered quickly to pre-drought levels, modeled total ecosystem carbon stock (above and below ground) does not recover even ~20 years after the maximum drought anomaly, falling to as much as two standard deviations below pre-drought levels during this period. Furthermore, to the extent that the modeled regional carbon stock recovers, it is nearly entirely driven by atmospheric CO2 trends rather than the precipitation recovery. Uncertainties in ecosystem carbon simulation are high in this region, as the models’ carbon responses to drought displayed a nearly 10-standard deviation spread. Nevertheless, the multi-model average response highlights the strong and persistent impact of drought on terrestrial carbon storage, and the potential risks of relying on terrestrial ecosystems as a “natural climate solution” for climate change mitigation.

Learn more here: Rigatti et al. 2024

Climate mitigation and adaptation for rice-based farming systems in the Red River Delta, Vietnam

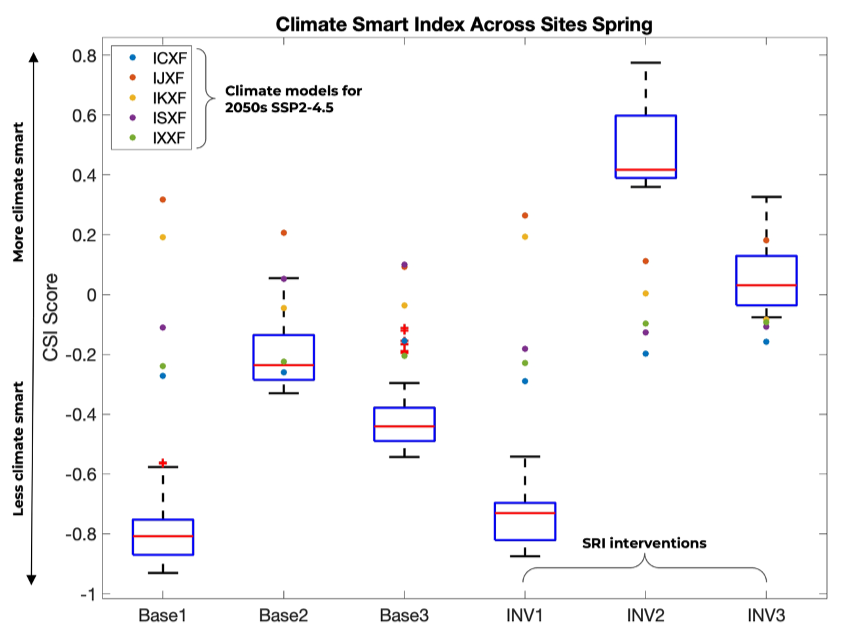

Climate smart index. Boxplots show the distribution across management-sites for baseline management and for the three interventions. Red plus signs indicate distributional outliers for the boxplots. The overplotted dots signify mean values across the management-sites for each of the five climate models (simulating SSP2-4.5 for 2050 conditions) identified in the Methods and also in the legend. CSI values closer to +1 indicate higher rice water productivity and reduced CH4 intensity – or more “climate smart” - while values closer to -1 indicate less climate smart.

Background: Rice is a major contributor to anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and is severely impacted by the resulting regional climate changes. Identifying crop management interventions to reduce GHG emissions in rice systems while improving productivity is, therefore, critical for climate change mitigation, adaptation, and food security. However, it can be challenging to conduct multivariate assessments of rice interventions in the field owing to the intensiveness of data collection and/or the challenges in considering changing climate conditions. Process-based modeling, evaluated against site-based data, provides an entry point for evaluating the impacts of climate change on rice systems and assessing the impacts, co-benefits, and trade-offs of interventions under historical and future climate conditions. Methods: We conduct an integrated assessment using a suite of coupled crop-soil model experiments for 83 rice sites across the Red River Delta, Vietnam, leveraging existing site-based management data. We test three alternative rice management interventions with our coupled crop-soil model, characterized by Alternate Wetting and Drying water management and other principles representing the System of Rice Intensification. Our simulations are forced with historical and future climate conditions represented by five Earth System Models for a medium-ambition climate scenario centered on the year 2050. We evaluate how these interventions compare for multiple biophysical variables and their efficacy under historical and future climate change.

Results: Overall, two SRI interventions increased yields by 50%+ under historical climate conditions while lowering (or not increasing) methane emissions. These interventions also increase yields under future climate conditions relative to baseline management practices, although overall yield declines across all management practices. Yield improvements are also accompanied by improved crop water-use efficiency. However, impacts on methane emissions were mixed across the sites under future climate conditions. Two of the interventions resulted in increased methane emissions, depending on the baseline management point of comparison. However, one intervention consistently reduced methane under historical and future climate conditions and relative to all baseline management systems, although there was considerable variation across five selected climate models.

Conclusions: AWD and SRI management principles combined with high-yielding varieties, implemented for site-specific conditions, can serve climate adaptation and mitigation goals under historical climate conditions. However, more uncertainty surrounds their ability to serve mitigation under future climate changes. Future work should better bracket important sensitivities of coupled crop-soil models and disentangle which management and climate factors drive the responses shown. Furthermore, future analyses that integrate these findings into socio-economic assessment can better inform if and how SRI/AWD can potentially benefit farmer livelihoods now and in the future.

Learn more here: Li et al. 2024

4) How do we better and more equitably represent the distributional impacts of environmental change on countries, species (human and non-human animals), and ecosystems?

Regional equity in high-impact climate research

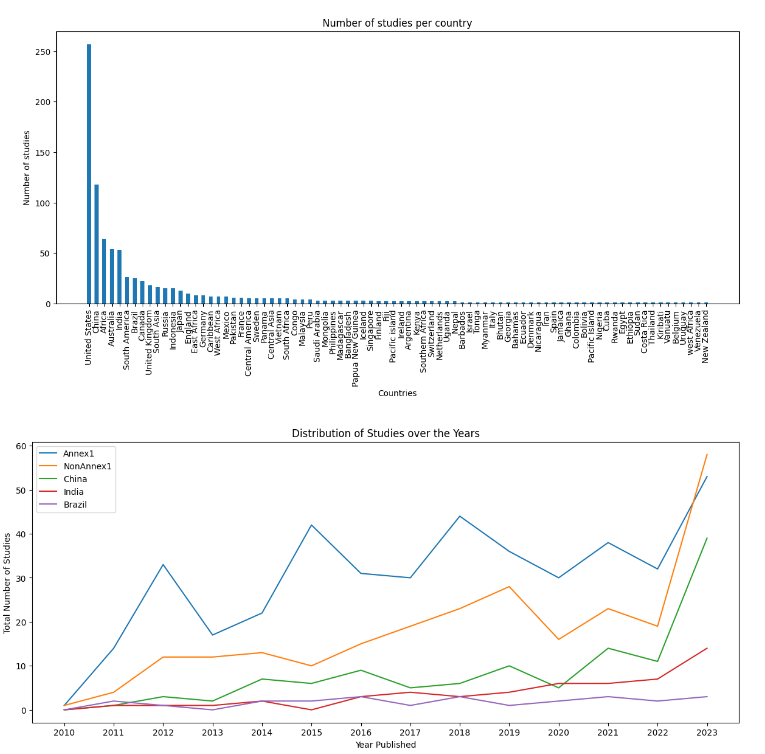

Number of papers found per region by year (a) and totaled by country across the 10 year period (b). (a) China, India and Brazil totals standalone and are not included in the non-Annex 1 total. Included in these totals are all climate change impact studies spanning Nature, Nature Climate Change, PNAS, Science and Science Advances (N=3921)

Ongoing climate change and extreme events have distributed impacts, disproportionately falling on developing and vulnerable regions. Our understanding of these regions’ climate impacts and options for adaptation is largely informed by peer-reviewed research. Research that makes it to the upper-tier academic journals most often has the highest “impact”, potentially guiding decision-making on climate action, including rising calls to attribute losses and damages. It is therefore crucial that strong research on disproportionately impacted regions appears in these high-impact journals. However, it is unclear (a) to what extent top-tier academic journals publish climate change research on the most vulnerable regions and (b) to what extent these regions’ authors and institutions are represented in these publications. To address these objectives, we employ data science techniques to construct and statistically analyze a dataset of the last decades’ climate research publications, using the provided metadata and complete manuscript texts as data, from top-tier journals. The results of this work will be communicated to increase equity and representation of use-inspired science and academic publishing on regional climate change impacts and adaptation.

Sharma, McDermid, Singh, Bonikowski et al (in prep)